![]()

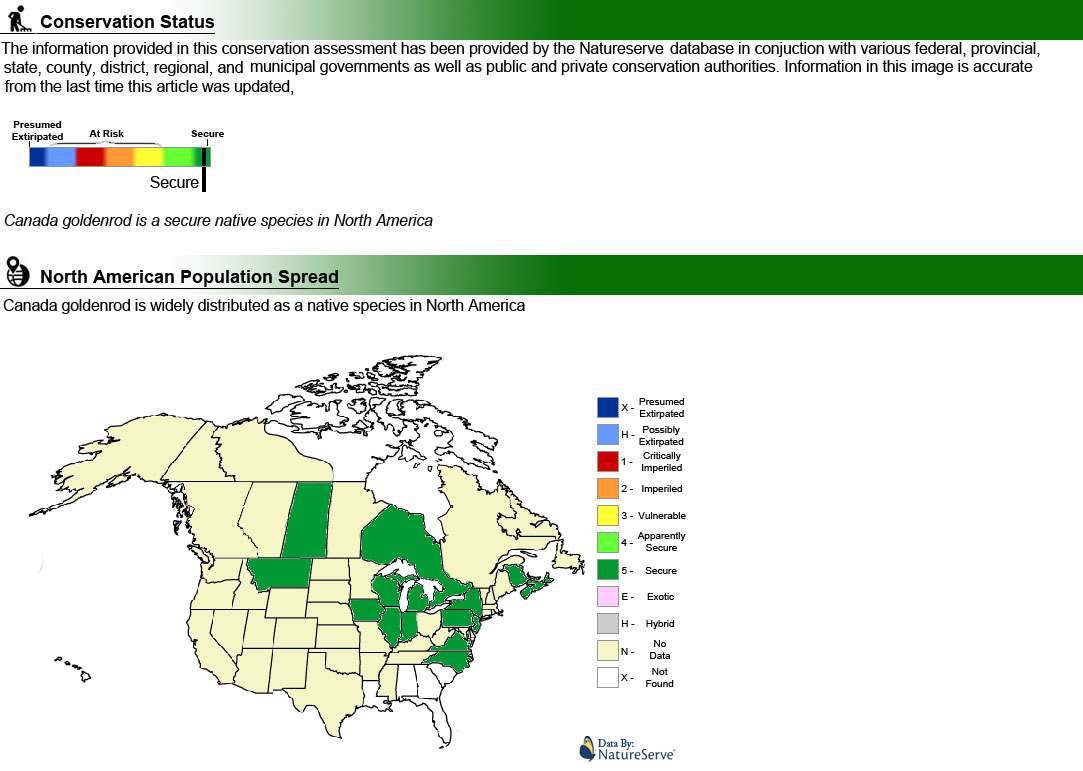

Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) is a prominent member of the goldenrod family (Solidago), a genus that includes approximately 100 to 120 species of flowering plants. These species are well-known for their bright golden-yellow flower clusters, which typically bloom from July through September, creating vibrant displays in meadows, roadsides, and disturbed areas. However, because of the visual similarities among goldenrod species, they can often be difficult to distinguish without close botanical examination.

Despite their widespread appeal, Canada Goldenrod and other goldenrod species are frequently—and incorrectly—blamed for causing hay fever in humans. This is a common misconception that persists largely because goldenrod blooms at the same time as ragweed, a plant whose pollen is a major allergen. The key difference is that goldenrod is insect-pollinated: its pollen is heavy and sticky, meant to be carried by bees, butterflies, and other pollinators. In contrast, ragweed is wind-pollinated, releasing large quantities of lightweight pollen into the air, which is the true culprit behind most late-summer allergy symptoms.

Culturally, goldenrods have held varied significance. In some traditions, they are viewed as symbols of good luck or good fortune. While they are often regarded as weeds in North America, particularly in agricultural or manicured landscapes, European gardeners have long valued goldenrod as an ornamental plant. In fact, British horticulturists adopted goldenrod into cultivated gardens well before it gained popularity in its native range, appreciating its hardiness, striking color, and value to pollinators.

Goldenrods also play an important ecological role. Their flowers serve as a critical nectar source for bees and butterflies, while their stems and leaves support the larvae of many Lepidoptera species (moths and butterflies). Some of these larvae induce the plant to form galls—swollen tissue masses that provide both food and shelter for the developing insect. These galls, in turn, attract parasitoid wasps, which use their ovipositors to penetrate the gall and lay eggs inside the larva. The wasp larvae feed on the host from within. Woodpeckers, drawn by the movement inside the galls, are known to peck them open and consume the insects inside, creating a fascinating multitrophic interaction among plants, herbivores, parasitoids, and predators.

However, outside its native range, Canada Goldenrod has become a highly invasive species, particularly in parts of Asia. In eastern and southeastern China—including the provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Shanghai—its spread has reached pandemic proportions, raising serious ecological and agricultural concerns. Reports from Shanghai have documented the local extinction of at least 30 native plant species due to competition from invasive goldenrod. In Ningbo, Zhejiang province, its presence has been linked to declining orange harvests, highlighting its impact on local agriculture. The plant continues to spread westward, with recent sightings as far inland as Yunnan province, prompting high alert among national and provincial authorities.

In Japan, Canada Goldenrod has become particularly widespread in Fukushima, where it has colonized abandoned rice fields left fallow following the 2011 nuclear disaster. Without human maintenance or agricultural competition, the plant has taken over vast areas, contributing to changes in local biodiversity and land use patterns. While Canada Goldenrod remains an important native species in North America, supporting a variety of pollinators and playing a role in natural ecosystems, its behavior as an aggressive invader abroad illustrates the complexity of plant introductions and the importance of managing invasive species to protect native flora and agricultural productivity.

![]()

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) has been explored for several commercial and industrial applications, one of the most unusual being its potential use as a natural source of rubber. Certain species of goldenrod produce latex, a milky sap that can be processed into rubber. This idea was famously investigated by inventor Thomas Edison in the early 20th century, who cultivated goldenrod plants over 3 meters tall in an effort to maximize latex production. Edison hoped to develop a domestic source of rubber in response to shortages during wartime.

However, while rubber can be extracted from goldenrod, it has significant limitations. Most notably, goldenrod-derived rubber has poor tensile strength, meaning it lacks the elasticity and durability required for most industrial applications. As a result, despite its novelty and early experimentation, goldenrod rubber has never been adopted on a large commercial scale and remains more of a historical curiosity than a practical resource.

On the other hand, goldenrod continues to enjoy popularity in the herbal and natural health market, especially in the form of goldenrod tea. This tea is made from the dried leaves and flowers of the plant and is commonly found in health food stores and herbal apothecaries. It is traditionally consumed for its diuretic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. Herbalists have long used goldenrod tea to support urinary tract health, alleviate seasonal allergies, and soothe sore throats or inflammation.

![]() Within both rational and holistic systems of medicine, plants in the Solidago genus, commonly known as goldenrods, have long held a place in traditional herbal practices, particularly for their role in supporting kidney and urinary tract health. Herbal practitioners have used goldenrod as a key ingredient in kidney tonics, designed to help reduce inflammation and soothe irritation caused by bacterial infections, urinary tract issues, or kidney stones. The plant’s diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties are believed to help flush out the urinary system, alleviating discomfort while promoting healing.

Within both rational and holistic systems of medicine, plants in the Solidago genus, commonly known as goldenrods, have long held a place in traditional herbal practices, particularly for their role in supporting kidney and urinary tract health. Herbal practitioners have used goldenrod as a key ingredient in kidney tonics, designed to help reduce inflammation and soothe irritation caused by bacterial infections, urinary tract issues, or kidney stones. The plant’s diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties are believed to help flush out the urinary system, alleviating discomfort while promoting healing.

In more intensive herbal detoxification protocols, goldenrod has been used as part of a cleansing tincture to support the kidneys and bladder during a healing fast. These regimens often combine goldenrod with potassium-rich vegetable broths and carefully selected juices, working together to encourage gentle elimination of toxins from the body and support overall urinary function. These traditional uses reflect goldenrod’s broad therapeutic potential, spanning both internal and external applications. While modern clinical studies are limited, goldenrod remains a valued remedy in herbal medicine for its effectiveness in soothing inflammation, cleansing the urinary tract, and providing mild analgesic effects in natural healing systems.

Please note that MIROFOSS does not suggest in any way that plants should be used in place of proper medical and psychological care. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

Canada Goldenrod, like many members of the goldenrod family, is considered edible and has a long history of culinary and medicinal use, particularly among Indigenous peoples of North America. Native American tribes utilized various parts of the plant for both nutritional and medicinal purposes. In particular, the seeds of certain goldenrod species were gathered and eaten, either raw or lightly processed. While small, these seeds could be roasted, ground, or mixed with other foraged ingredients to create nourishing meals or to supplement other foods during times of scarcity.

Goldenrod also has a place in traditional herbal preparations. Teas made from goldenrod leaves and flowers have been consumed for their medicinal benefits, including use as a diuretic, a mild anti-inflammatory, and a remedy for respiratory ailments such as colds or sore throats. These herbal infusions are known to have a slightly bitter, astringent taste, often blended with other herbs to enhance flavor and therapeutic effect.

In the realm of apiculture, goldenrod is a valuable late-season nectar source for bees, especially in late summer and early fall when few other plants are in bloom. However, honey derived from goldenrod nectar is often noted for its distinctively dark color and strong, sometimes pungent flavor. This intensity is usually due to admixtures of nectar from multiple late-blooming plants, as bees tend to forage widely. While the taste may not appeal to everyone, goldenrod honey is prized by many for its richness, complexity, and robust mineral content. Though not a staple food, early goldenrod offers diverse uses, from traditional foods and teas to medicinal infusions and flavorful honey, making it a versatile and culturally significant wild plant.

Please note that MIROFOSS can not take any responsibility for any adverse effects from the consumption of plant species which are found in the wild. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) is a widespread and adaptable wildflower commonly found throughout North America, where it thrives in a variety of open and semi-open habitats. It is most often seen in meadows, pastures, lightly forested woodlands, roadsides, and even abandoned or uncultivated lands. These environments provide the sunlight and soil conditions that favor its vigorous growth and ability to spread. While Solidago canadensis is native to North America, a few other goldenrod species are native to South America and parts of Eurasia, giving the genus Solidago a global presence, albeit concentrated in temperate regions.

Despite being a native species and an important contributor to local ecosystems, Canada Goldenrod is often viewed as a weed by gardeners, landscapers, and farmers—particularly because of its tendency to spread aggressively and dominate disturbed areas. Its robust root system and prolific seed production allow it to quickly colonize open ground, which can make it difficult to manage in more controlled or ornamental settings. Nonetheless, it remains highly valuable to pollinators and plays a critical role in supporting biodiversity.Moist conditions are tolerated, if the soil is reasonably well-drained. Suitable for: light (sandy), medium (loamy) and heavy (clay) soils. This soil adaptability, combined with their resilience to varying moisture levels and sun exposure, makes goldenrods well-suited to naturalized plantings, restoration projects, and wildflower gardens—particularly in areas where low-maintenance, native vegetation is desired.

| Soil Conditions | |

| Soil Moisture | |

| Sunlight | |

| Notes: |

![]()

Canada Goldenrod is a tall, upright perennial herb that can reach heights of up to 200 centimeters (approximately 6.5 feet), making it one of the more robust species within the goldenrod genus. The plant typically grows unbranched, except near the top where the flowering structure begins to form. Its central stem is slightly ridged, smooth, and hairless, usually colored green, although it may develop a reddish hue in some conditions.

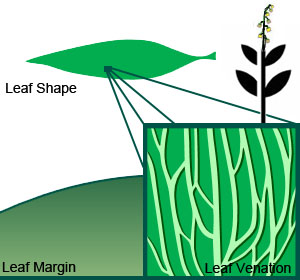

The leaves are arranged alternately along the stem and are lanceolate in shape—long, narrow, and tapering to a point. Lower leaves can be up to 20 centimeters long and 3 centimeters wide, but they become progressively smaller as they ascend the stem. The leaf margins are either entire (smooth) or slightly serrated, and while the surfaces are generally hairless, some may have tiny, fine hairs along the edges.

The plant’s most distinctive feature is its inflorescence—a pyramidal panicle that can range from 5 to 40 centimeters tall and nearly as wide. This flowering structure consists of numerous horizontal branches, each lined on the upper side with a dense array of tiny golden-yellow flower heads. These flower heads are about 3 millimeters in both length and width and are densely packed, giving the entire inflorescence a rich, feathery appearance. Depending on the population or growing conditions, the panicle may appear broad and spreading or narrow and more compact.

The flowers may emit a mild, pleasant fragrance and are highly attractive to a wide range of pollinators, especially bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects. Canada Goldenrod typically blooms from mid- to late summer, with a flowering period that lasts between one and two months. Following pollination, the plant produces small fruits known as achenes—dry, one-seeded structures. Each achene is equipped with a tiny tuft of silky hairs, known as a pappus, which helps the seeds disperse over long distances via the wind, contributing to the plant’s reputation for vigorous and widespread colonization.

The root system is composed of a short, woody caudex, especially in mature plants. From this base, rhizomes (underground horizontal stems) extend outward, giving rise to vegetative offshoots. This ability to spread both by seed and rhizome makes Canada Goldenrod particularly effective at forming dense colonies, which can outcompete surrounding vegetation if not managed.

![]()

| Plant Height | 60cm to 200cm |  |

| Habitat | Fields, Roadsides, Waste places | |

| Leaves | Lanceolate | |

| Leaf Margin | Entire | |

| Leaf Venation | Longitudinal | |

| Stems | Smooth Stems | |

| Flowering Season | August to October | |

| Flower Type | Elongated clusters of bell shaped florets | |

| Flower Colour | Yellow | |

| Pollination | Bees, Insects | |

| Flower Gender | Flowers are hermaphrodite and the plants are self-fertile | |

| Fruit | Tufted Seeds | |

| USDA Zone | 3A (-37.3°C to -39.9°C) cold weather limit |

![]()

No known health risks have been associated with Canada goldenrod. However ingestion of naturally occurring plants without proper identification is not recommended.

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see an artist rendering, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of Canada goldenrod. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see a magnified view, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of the seeds created by Canada goldenrod for propagation. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

Canada Goldenrod can be referenced in certain current and historical texts under the following two names:

![]()

|

What's this? What can I do with it? |

![]()

| Dickinson, T.; Metsger, D.; Bull, J.; & Dickinson, R. (2004) ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto:McClelland and Stewart Ltd. | |

| Blanchan, Neltje (2005). Wild Flowers Worth Knowing. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. |

|

| Kartesz, J.T. 1994. A synonymized checklist of the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. 2nd edition. 2 vols. Timber Press, Portland, OR. | |

| "Goldenrod Rubber". Time Magazine. December 16, 1929. | |

| Campion, K. (1995). Holistic Woman's Herbal - How to Achieve Health and Well-Being at Any Age. Barnes & Noble, Inc. 1995. ISBN 978-0-7607-1030-2 | |

| Kartesz, J.T. 1996. Species distribution data at state and province level for vascular plant taxa of the United States, Canada, and Greenland (accepted records), from unpublished data files at the North Carolina Botanical Garden, December, 1996. | |

| MacKinnon, Kershaw, Arnason, Owen, Karst, Hamersley, Chambers. 2009. Edible & Medicinal Plants Of Canada ISBN 978-1-55105-572-5 |

|

| USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. Wetland flora: Field office illustrated guide to plant species. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| May 31, 2025 | The last time this page was updated |

| ©2025 MIROFOSS™ Foundation | |

|

|